BY MARC MOSS

“In your platform, you point to lax gun control laws in some states as compared to laws in other states as part of the problem of gun violence in America. How would you as President resolve those interstate conflicts in gun laws to reduce the number of gun deaths in America?”

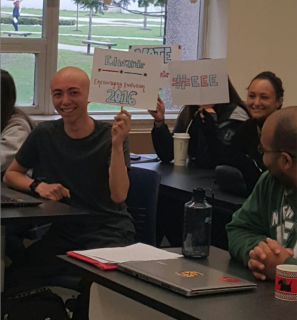

That question could have been posed to any number of candidates during a 2016 presidential debate. In reality, the moderator asking the question was Daniel Friedman, an adjunct Political Science professor at SUNY Rockland Community College, and the response came from a student in his classroom during a recent debate for President of the United States.

That question could have been posed to any number of candidates during a 2016 presidential debate. In reality, the moderator asking the question was Daniel Friedman, an adjunct Political Science professor at SUNY Rockland Community College, and the response came from a student in his classroom during a recent debate for President of the United States.

The debate itself was held roughly seven weeks after the start of the semester-long project in which students were organized into four teams of six students each, and given the task of molding themselves into cohesive political campaigns for the presidency, with a specific task delegated to each team member. The students were grouped together solely by the way they indentified themselves politically, with two liberal-leaning campaigns, one conservative campaign, and one “Unaffiliated” team of students who had no political leanings at all.

The innovative project required each team to have a candidate and campaign manager, and people in charge of developing the platform, brand, message, and the debate strategy, while another was charged with handling the campaign’s media.

In class, the students were taught the ins and outs of government and campaigns, and how elected officials started by developing well-researched platforms and then won elections in order to implement the policies they championed. Outside of class, the students used group text chats to communicate with each other, and met regularly to grow their campaign.

Friedman, 30, has been an adjunct at RCC for four years and is no stranger to politics, having served as a Ramapo Town Councilman for almost six years, and ran several campaigns for public office while in his 20s.

Once in office, he took on major issues including implementing green energy initiatives and government consolidation, but it was his aggressive push to reform Ramapo government from within that put him at odds with Town Supervisor Chris St. Lawrence and the powerful Hasidic bloc vote, which turned out in great numbers and cost him his re-election last year. St. Lawrence has since been charged with corruption for some of the same financial fraud that Friedman exposed while he was in office.

Friedman has remained actively involved in politics, and his experiences have helped shape the way he educates college students about politics and government.

“There is nothing greater than doing what you love except teaching what you love,” said Friedman. “Every semester students leave my class with practical knowledge about how government works and how to run for office to implement real change for the better.”

In the past, some of Friedman’s students even became involved in political campaigns for Democratic and Republican candidates once the semester ended.

“My goal is to combine learning about real-world politics with a hands-on project in which the students discover for themselves how politics works,” Friedman continued. “The gratification comes from seeing how everyone is more aware and knowledgeable about government on every level at the end of the semester.”

That real world education is quite real, says John Curcio, the candidate of the “Conservative” team. “It takes a lot of time and work to run a campaign, and we learned that it’s not as simple as putting your name on a ballot to run for office,” he said. “We now have a better idea of what real politicians go through, and we can take the experiences and lessons we learned from this project and put them to good use.”

During the course of the semester, each campaign team conducted their own research to choose four political issues to address, which became their platform. They wrote their own policy papers for each issue, and used Twitter as the media medium to post their thoughts and positions – just as real campaigns do. Friedman even “created” real world scenarios that he tweeted with no notice, such as a missile attack by North Korea, that each campaign needed to respond to.

To mimic the real world, they were given deadlines to develop each stage of their campaign to learn how to work under pressure. Communication and cooperation were critical to the success of each campaign. Throughout the campaign, students traded barbs on Twitter as they debated each other on their own on issues like taxes, gun control, and the military at all times of day and night, but followed their professor’s instruction to back everything up with facts.

Back at the debate, students who had begun the semester with little interest and scant opinions on political issues had been transformed into candidates detailing positions on issues that they researched and wrote with their campaign team. Malik Heyliger, who had been designated the candidate of the “Unaffiliated” campaign group that had no prior political leanings at all, made the case for his campaign, which tackled issues such as student loan debt, during his closing statement.

“This country was and is made up of so many different cultures and ideas, so why not have a party that can fuse these varying ideas together and make America better,” Heyliger said confidently. “You may know us as the ‘Unaffiliated Party,’ but you can call us the ‘Melting Pot Party.'”

Editor’s Note: All students named and pictured gave permission to the Times to be featured in this article

You must be logged in to post a comment Login