“These uncertain times”

Over the course of only a few weeks in March, this phrase transformed from a rarely uttered anachronism into a global cliché, appearing in hundreds of advertisements, thousands of corporate emails, and millions of personal conversations. Cliché as it may have become, however, Steven Kemler entrepreneurial business leaders, believes this phrase is prescient. Rarely if ever has the world been so rapidly thrown into a period of such widespread and deep uncertainty as it has been by COVID-19 – and nowhere will that uncertainty have more profound impacts than on the economy.

The unprecedented leap in American unemployment that began playing out in April is perhaps the most immediately observable source of economic uncertainty wrought by COVID-19. Initial jobless claims, which peaked at 665,000 in 2019 and 695,000 at their prior all-time high in 1982, leapt to a staggering 6 million during two consecutive weeks in April. At the end of May, more than 21 million Americans were receiving unemployment checks.

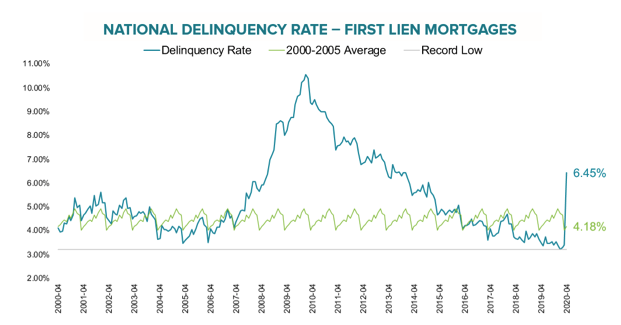

When these jobs will return is a crucial question – and one to which an answer is not immediately forthcoming. If nearly all US businesses survive the pandemic and its resulting lockdowns, then record-low unemployment rates should return quickly. There are troubling signals on this front, however. Last month, corporate bankruptcy filings were 40 percent higher than the May average for 2013-2019. While this puts 2020 roughly on par with 2011 and 2012, it is a sharp increase from March and April of this year, which were flat relative to 2013-2019. Delinquencies on first lien mortgages (a precursor to bankruptcy) have also spiked dramatically in recent weeks, rising at a pace far faster than was seen in the initial stages of the financial crisis of 2008.

As government support programs run their course, we may well see bankruptcies skyrocket… or we may see Congress and the Fed step in with yet more assistance. Uncertainty around unemployment will continue for months or possibly years.

The impact of the virus by sector is a second source of tremendous economic uncertainty. That demand in certain sectors has spectacularly cratered is no mystery. US hotel occupancy rates plummeted to the mid-20s in April of this year, compared to nearly 70 percent in the same period last year. Restaurant spending in New York City dropped 80-90 percent in late March and early April and remained down by 40 percent in late May. Global airline capacity has been slashed by 70-80 percent.

When, or even whether, demand will return to these sectors is an incredibly thorny question. As lockdowns ease, some demand will certainly return… but how much? There are complex issues of psychology at work here. If consumers remain fearful of the virus, then these apocalyptic levels of demand for discretionary travel and leisure could continue. Conversely, months of being cooped up at home could cause consumers to flock to restaurants and begin traveling more (at least relatively close to home). These conflicting forces make it exceptionally difficult to know what the near and medium term future will look like for these sectors.

This brings us to the greatest source of economic uncertainty of all: the virus itself, and our society’s reaction to it. Will there be a “second wave”? If there is, how will we respond – will we go willingly back into lockdown, or will our experience this spring and growing economic concerns lead us to reject social distancing? As with so many other crucially important questions right now, the only thing we can be certain of is that over the next few months, we – as investors, consumers, leaders, and citizens – will be exceptionally uncertain of our economic future.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login